The Shenanigans of Robert Moses

Some time in the beginning of 2020 I watched Motherless Brooklyn, Edward Norton’s latest directorial effort. The film is… a mixed bag, it’s an adaptation of the book of the same name by Jonathan Lethem, but most of the key plot points have been significantly altered by Norton. I haven’t read the book, but I assume at this point the similarities between it and the film are scarce.

It’s also quite long, clocking in at almost two and a half hours. Its critical reception has been lukewarm, and dare I say the film will be forgotten before long. The most fascinating part to me was the urban renewal plot introduced by Norton, which features Moses Randolph, a city planner played by Alec Baldwin.

Moses (Alec Baldwin) face-to-face with our protagonist (played by Norton)

Randolph is based on the New York City planner, Robert Moses, who I didn’t hear of until after I watched the film. The character is fictional, of course, but there are many similarities to the real Moses, such as his relationship with his brother (played by Willem Dafoe in the film), his above-everyone attitude, and the unmistakable power and influence. The Wikipedia page for Moses is pretty encompassing, but his influence over New York fascinated me so much that I wanted to find more. I mean, how could a single person, not even elected to public office, and mostly forgotten by now, have had so much power?

Turns out there’s a book called The Power Broker, a Pulitzer-winning biography of Moses written by Robert Caro, one of the most important biographers of our times. At 1336 pages, it could also be used as a deadly weapon, but I managed to find a digital copy that I’ve been reading on my Kindle. Fun fact: Caro’s original manuscript ran to about 1 million words, but was cut down to about 700,000. He’s like the non-fiction Stephen King.

It took me almost a year, but I’m proud to say I finally finished it. Moses was a smart guy, bending laws to suit his will and creating numerous public authorities that gave him and his projects financial independence. He was also a piece of shit and a racist, who basically did what he wanted regardless of public opinion. Mayors, governors, other public officials couldn’t tell him shit, they all had to bow down to his way of doing things. He was that powerful. He razed neighborhoods to build expressways, built roads through parks, intentionally designed parkways to have low bridges to prevent travel by bus (stupid bus riders, they should be rich enough to have cars). In a depressing turn of events, his plans to have a Brooklyn-Battery bridge built were thwarted by President Roosevelt himself.

Caro is like a walking thesaurus though, for that I’ve decided to share some clippings that made an impression on me (it’s a thousand-page book, so there are a lot of clippings).

- Not directly related to Moses, but about the robber barons, who built large country estates for themselves in Long Island (a period and setting also immortalized in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby)

Highlight on Page 207 | Loc. 3160-69 | Added on Wednesday, June 03, 2020, 01:32 AM

These were the men who, during the “Middle Ages of American industry,” the half century of unbridled industrial expansion following the Civil War, had harnessed America’s vast mineral resources and tapped its long-stored capital to create needed industrial growth but who, to turn that growth into personal wealth, had stationed themselves at the “narrows” of production, the key points of production and distribution, and exacted tribute from the nation. They were the men who had blackmailed state legislatures and city councils by threatening to build their railroad lines elsewhere unless they received tax exemptions, outright gifts of cash—and land grants so vast that, by 1920, the elected representatives of America had turned over to the railroad barons an area the size of Texas. They were the men who had bribed and corrupted legislators—the Standard Oil Company, one historian said, did everything possible to the Pennsylvania Legislature except refine it—to let them loot the nation’s oil and ore, the men who, building their empires on the toil of millions of immigrant laborers, had kept wages low, hours long, and had crushed the unions. Their creed was summed up in two quotes: Commodore Vanderbilt’s “Law? What do I care for law? Hain’t I got the power?” and J. P. Morgan’s “I owe the public nothing.”

- Moses was adored by the press and the public for his ardent support of parks. Who doesn’t love parks?

Highlight on Page 302 | Loc. 4620-23 | Added on Saturday, June 06, 2020, 12:33 AM

This lesson Robert Moses would often recite to associates. He would put it this way: As long as you’re fighting for parks, you can be sure of having public opinion on your side. And as long as you have public opinion on your side, you’re safe. “As long as you’re on the side of parks, you’re on the side of the angels. You can’t lose.”

- How to get your projects funded 101 as taught by Robert Moses

Highlight on Page 303 | Loc. 4634-46 | Added on Saturday, June 06, 2020, 12:36 AM

Misleading and underestimating, in fact, might be the only way to get a project started. Since his projects were unprecedentedly vast, one of the biggest difficulties in getting them started was the fear of public officials— not only upstate conservatives but liberal public officials as well—concerned with the over-all functioning of the state that the state couldn’t afford the projects, that the projects, beneficial though they might be, would drain off a share of the state’s wealth incommensurate with their benefits. But what if you didn’t tell the officials how much the projects would cost? What if you let the legislators know about only a fraction of what you knew would be the projects' ultimate expense? Once they had authorized that small initial expenditure and you had spent it, they would not be able to avoid giving you the rest when you asked for it. How could they? If they refused to give you the rest of the money, what they had given you would be wasted, and that would make them look bad in the eyes of the public. And if they said you had misled them, well, they were not supposed to be misled. If they had been misled, that would mean that they hadn’t investigated the projects thoroughly, and had therefore been derelict in their own duty. The possibilities for a polite but effective form of political blackmail were endless. Once a Legislature gave you money to start a project, it would be virtually forced to give you the money to finish it. The stakes you drove should be thin-pointed—wedge-shaped, in fact—on the end. Once you got the end of the wedge for a project into the public treasury, it would be easy to hammer in the rest.

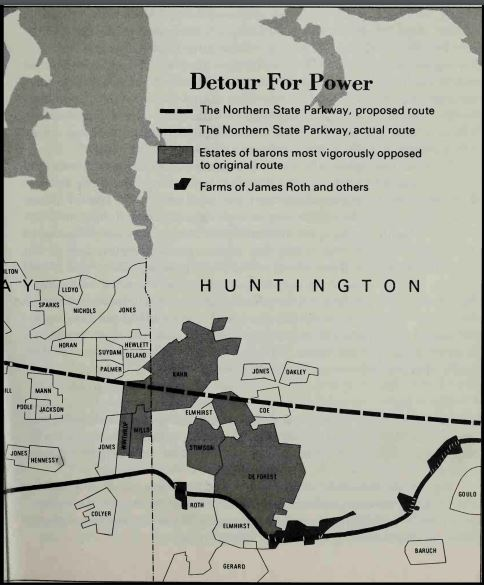

- Moses is happy to move his roads for rich people, but not for the working class. Also, the consequences of this.

Highlight on Page 392 | Loc. 6000-6005 | Added on Sunday, June 14, 2020, 01:46 AM

Robert Moses had shifted the parkway south of Otto Kahn’s estate, south of Winthrop’s and Mills’s estates, south of Stimson’s and De Forest’s. For men of wealth and influence, he had moved it more than three miles south of its original location. But James Roth possessed neither money nor influence. And for James Roth, Robert Moses would not move the parkway south even one tenth of a mile farther. For James Roth, Robert Moses would not move the parkway one foot. Robert Moses had offered men of wealth and influence bridges across the parkway so that there would be no interference with their pleasures. But he wouldn’t offer James Roth a bridge so that there would be no interference with his planting.

Highlight on Page 423 | Loc. 6484-90 | Added on Monday, June 15, 2020, 01:20 AM

The long-term costs to the public of Moses' accommodation include figures that cannot be prefaced with dollar signs. For one thing, the accommodation condemned users of the parkway to a perpetual detour of five miles around the Wheatley Hills. Coupled with the six-mile detour forced on parkway users by Moses' previous accommodation with Otto Kahn and the other Dix Hills barons, it meant that a commuter who lived anywhere east of Dix Hills and who used the parkway to get to his job in New York City was condemned to drive, every working day of his life, twenty-two extra and unnecessary miles. He had to drive no unnecessary miles per week, 5,500 per year—all because of Moses' “compromise.” By the 1960’s there were about 21,500 such commuters, and the cost to them alone of Moses' accommodation totaled tens of millions of wasted hours of human lives.

- On the racism and self-perceived superiority of Moses

Highlight on Page 447 | Loc. 6850-60 | Added on Tuesday, June 16, 2020, 12:17 AM

He had restricted the use of state parks by poor and lower-middle-class families in the first place, by limiting access to the parks by rapid transit; he had vetoed the Long Island Rail Road’s proposed construction of a branch spur to Jones Beach for this reason. Now he began to limit access by buses; he instructed Shapiro to build the bridges across his new parkways low—too low for buses to pass. Bus trips therefore had to be made on local roads, making the trips discouragingly long and arduous. For Negroes, whom he considered inherently “dirty,” there were further measures. Buses needed permits to enter state parks; buses chartered by Negro groups found it very difficult to obtain permits, particularly to Moses' beloved Jones Beach; most were shunted to parks many miles further out on Long Island. And even in these parks, buses carrying Negro groups were shunted to the furthest reaches of the parking areas. And Negroes were discouraged from using “white” beach areas—the best beaches—by a system Shapiro calls “flagging”; the handful of Negro lifeguards (there were only a handful of Negro employees among the thousands employed by the Long Island State Park Commission) were all stationed at distant, least developed beaches. Moses was convinced that Negroes did not like cold water; the temperature at the pool at Jones Beach was deliberately icy to keep Negroes out.

Highlight on Page 721 | Loc. 11042-55 | Added on Tuesday, July 14, 2020, 10:55 PM

Robert Moses built 255 playgrounds in New York City during the 1930’s. He built one playground in Harlem. An overspill from Harlem had created Negro ghettos in two other areas of the city: Brooklyn’s Stuyvesant Heights, the nucleus of the great slum that would become known as Bedford-Stuyvesant, and South Jamaica. Robert Moses built one playground in Stuyvesant Heights. He built no playgrounds in South Jamaica. “We have to work all day and we have no place to send the children,” one Harlem mother had written before Robert Moses became Park Commissioner. “There are kids here who have never played anyplace but in the gutter.” She could have written the same words after he had been Park Commissioner for five years. After a building program that had tripled the city’s supply of playgrounds, there was still almost no place for approximately 200,000 of the city’s children—the 200,000 with black skin—to play in their own neighborhoods except the streets or abandoned, crumbling, filthy, looted tenements stinking of urine and vomit; or vacant lots carpeted with rusty tin cans, jagged pieces of metal, dog feces and the leavings, spilling out of rotting paper shopping bags, of human meals. Children with white skin had been given swings and seesaws and sliding ponds. Children with black skin had been left with the old broomsticks that served them as baseball bats. Children with white skin had been given wading pools to splash in in summer. If children with black skin wanted to escape the heat of the slums, they could remove the covers from fire hydrants and wade through their outwash, as they had always waded, in gutters that were sometimes so crammed with broken glass that they glistened in the sun. Negroes begged for playgrounds.

Highlight on Page 726 | Loc. 11123-46 | Added on Tuesday, July 14, 2020, 11:06 PM

The ingenuity that Robert Moses displayed in building swimming pools was not restricted to their design. Moses built one pool in Harlem, in Colonial Park, at 146th Street, and he was determined that that was going to be the only pool that Negroes— or Puerto Ricans, whom he classed with Negroes as “colored people”— were going to use. He didn’t want them “mixing” with white people in other pools, in part because he was afraid, probably with cause, that “trouble”—fights and riots—would result; in part because, as one of his aides puts it, “Well, you know how RM felt about colored people.” The pool at which the danger of mixing was greatest was the one in Thomas Jefferson Park in La Guardia’s old East Harlem congressional district. This district was white, but the pool, one block in from the East River, was located between 111th and 114th streets. Not only was it close to Negro Harlem, but the city’s Puerto Rican population, while still small, was already beginning to outgrow the traditional boundaries of “Spanish Harlem” just north of Central Park and to expand toward the east— toward the pool. By the mid-Thirties, Puerto. Ricans had reached Lexington Avenue, only four blocks away, and some had begun moving onto Third Avenue, only three blocks away. To discourage “colored” people from using the Thomas Jefferson Pool, Moses, as he had done so successfully at Jones Beach, employed only white lifeguards and attendants. But he was afraid that such “flagging” might not be a sufficient deterrent to mothers and fathers from the teeming Spanish Harlem tenements who would be aware on a stifling August Sunday that cool water in which their children could play was only a few blocks away. So he took another precaution. Corporation Counsel Windels was astonished at its simplicity. “We [Moses and I] were driving around Harlem one afternoon—he was showing me something or other—and I said, ‘Don’t you have this problem with the Negroes overrunning you?’ He said, ‘Well, they don’t like cold water and we’ve found that that helps.’ " And then, Windels says, Moses told him confidentially that while heating plants at the other swimming pools kept the water at a comfortable seventy degrees, at the Thomas Jefferson Pool, the water was left unheated, so that its temperature, while not cold enough to bother white swimmers, would deter any “colored” people who happened to enter it once from returning. Whether it was the temperature or the flagging—or the glowering looks flung at Negroes by the Park Department attendants and lifeguards— one could go to the pool on the hottest summer days, when the slums of Negro and Spanish Harlem a few blocks away sweltered in the heat, and not see a single non-Caucasian face. Negroes who lived only half a mile away, Puerto Ricans who lived three blocks away, would travel instead to Colonial Park, three miles away—even though many of them could not afford the bus fare for their families and had to walk all the way. The fact that they didn’t use their neighborhood pool—and the explanation for this fact—was never once mentioned by any newspaper or public speaker, or at least not by any public speaker prominent enough to have his speech reported in a newspaper.

Highlight on Page 821 | Loc. 12578-95 | Added on Tuesday, August 11, 2020, 12:43 AM

Robert’s concept of help was that of the mother he imitated, the patronizing “Lady Bountiful” who never forgot that the lower classes were lower. It was the concept of rigid class distinction and separation that would later be set in concrete by Robert Moses' public works. Paul, doted on by Grannie Cohen (and by her husband, Bernhard; on Saturdays, the gentle old man and the bright-eyed, handsome little boy would walk from the Moses brownstone on Forty-sixth Street down to the tip of Manhattan Island, where the grandfather would reward him with a nickel), understood exactly what the nickname “Lady Bountiful” implied. “Don’t you see that settlement-house attitude of hers in everything Mr. Robert does?” he would demand. “This ‘You’re my children and I’ll tell you what’s good for you’? " It was not his attitude. His brother wanted class distinctions made more rigid; Paul wanted them eliminated. His brother despised “people of color”; Paul’s attitude, in Mrs. Proper’s words, was “a genuine feeling of real indignation over the way Negroes were treated, and don’t forget, this was at a time when it wasn’t fashionable to have such feelings.” His brother’s attitude toward members of the classes Bella called “lower” was, like Bella’s, markedly patronizing; perhaps in reaction, Paul, says a friend, “was a person who would talk to some menial and be on fine terms with him. He could be impossible—opinionated, arrogant—with people on his own social plane. But he would never, never, act like that with anyone who couldn’t talk back to him. He was very much aware of the moral responsibility to the lower classes—he was like Robert in that. But his attitude towards these classes was genuinely friendly.” He had the ability— which Robert did not—to see people not as members of classes but as individuals. When they were well into their seventies, the two brothers would be asked about the maids, cooks and laundresses who had worked in the Forty-sixth Street brownstone. Robert could remember exactly one: “old Annie.” Asked to “tell me something about her,” he responded by listing her duties— and stopped. About this woman whom he saw almost every day of his boyhood, he knew nothing more—not even whether or not she was married. Paul remembered an even dozen who passed through the Moses household at one time or another—and, fifty years after he had last seen most of them, he could relate details of their personal lives to an extent that revealed he had talked to them as a friendly equal.

- Cheating the system

Highlight on Page 890 | Loc. 13640-44 | Added on Tuesday, September 15, 2020, 01:46 AM

The existence of the Triborough Authority “shall continue only until all its bonds have been paid in full,” the act said. But, because of Moses' amendments, the Authority no longer had to pay its bonds in full. Every time it had enough money to pay them in full, it could instead use the money to issue new bonds in their place. The amendments meant that unless it wanted to, the Authority wouldn’t ever have to turn its bridges over to the city. It might, if it so desired, be able to keep the bridges—and stay in existence—as long as the city stayed in existence.

- The Battery Crossing fight: Moses wanted a bridge, everyone else wanted a tunnel. By this time Moses was so powerful, that the President of the United States himself had to intervene. As revenge for losing this fight, he decided—out of spite—to effectively move the Aquarium from Battery Park to Coney Island. Imagine being that petty.

The planned, but ultimately unbuilt Brooklyn-Battery Bridge

Highlight on Page 908 | Loc. 13923-29 | Added on Thursday, September 17, 2020, 12:19 AM

With the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel firmly in his grasp, Moses made a slight modification in its design: It became the Brooklyn-Battery Bridge. The change reflected the importance Moses had come to place on bankers' values—a bridge could be built slightly more cheaply than a tunnel, would cost slightly less to operate and could, per dollar spent, carry slightly more traffic—and his eagerness to build impressive monuments to himself; a bridge was, after all, the most impressive of monuments (“the finest architecture made by man”) as well as one whose life was “measureless”; a tunnel, he said in public, “is merely a tiled, vehicular bathroom smelling faintly of monoxide”; in private, an aide recalls, “he used to say, ‘What’s a tunnel but a hole in the ground?'—and RM wasn’t interested in holes in the ground.”

Highlight on Page 917 | Loc. 14055-60 | Added on Thursday, September 17, 2020, 12:33 AM

According to some estimates, the portion of the city’s total real estate tax paid by Lower Manhattan was as high as 10 percent; large office buildings contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars annually to the city in real estate taxes. Reduce their light and air and they would be entitled to a substantial reduction in taxes. And Moses’ bridge would reduce the taxes for dozens of such buildings. Computing the depreciation in real estate values conservatively, Singstad found that, during the next twenty years alone, building the Battery Crossing as a bridge instead of as a tunnel would cost the city more than $29,000,000 in real estate taxes.

Highlight on Page 942 | Loc. 14439-43 | Added on Monday, September 21, 2020, 01:13 AM

If the Mayor did not immediately guarantee that there would be no Battery tunnel, Moses was saying, he, Moses, would never give him the money for a Battery bridge. Either guarantee immediately that Moses could build the Crossing—and build the kind of Crossing he wanted—or there wouldn’t be any Crossing. The telegram was not a request but an ultimatum, not an appeal from a subordinate to a superior, not a plea from a commissioner appointed by the Mayor that the Mayor change a decision, but a demand from someone who had the money to give the Mayor something he wanted.

Highlight on Page 947 | Loc. 14510-14 | Added on Tuesday, September 22, 2020, 12:20 AM

And then, in the seventh hour of the hearing, Robert Moses stood up to speak. Reading from a yellow legal pad on which he had been scribbling furiously during the opposition speeches, he turned his attention first to the analysis of the relative efficiency of civil service architects and private consultants. “I want to warn my friends in the civil service that civil service can become a racket,” he said. “It’s getting to be so that nothing will please them but a Communist state, which we know is so pleasing to Mr. Isaacs…”

Highlight on Page 952 | Loc. 14588-96 | Added on Tuesday, September 22, 2020, 12:33 AM

The Battery Crossing fight was also the moment of truth for the reformers in another respect. It made them see that their opposition no longer mattered to Moses. They had played a vital role in his acquisition of power in the city. Quite possibly, in fact, he could not have acquired that power without their help. But he had taken that power and used it to acquire more and more of it—and now, they suddenly realized, he had enough of it so that they could not take it back from him, could not, in fact, stop him from the absolutely untrammeled use of it. He no longer had to be concerned with their opinions—and he wasn’t concerned with their opinions. They were the city’s aristocracy. They had always had a voice—an important voice—in decisions vital to the city, a voice that was important to them because they cared about and loved the city. But in the areas that Robert Moses had carved out for his own, they would have a voice no longer. And neither would the city. For if the Battle of the Battery Crossing was a moment of truth for the reformers, it was also, although no one recognized it as such, a moment of truth for New York.

Highlight on Page 954 | Loc. 14624-34 | Added on Tuesday, September 22, 2020, 12:38 AM

In the April 5, 1939, edition of her newspaper column, “My Day,” Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt was enthusiastically discussing her grandchildren when she switched abruptly to one paragraph on a different topic. I have a plea from a man who is deeply interested in Manhattan Island, particularly in the beauty of the approach from the ocean at Battery Park. He tells me that a New York official, who is without doubt always efficient, is proposing a bridge one hundred feet high at the river, which will go across to the Whitehall Building over Battery Park. This, he says, will mean a screen of elevated roadways, pillars, etc., at that particular point. I haven’t a question that this will be done in the name of progress, and something undoubtedly needs to be done. But isn’t there room for some consideration of the preservation of the few beautiful spots that still remain to us on an overcrowded island? A single, small paragraph, on a subject she would not raise again. But revealing nonetheless, as the smallest ripple in a pond’s still water reveals the hidden trout below. For that paragraph was the ripple, the only ripple, that revealed that far below the surface of the public controversy over Robert Moses' huge bridge, down in the quiet, murky depths, impenetrable to the public gaze, in which real power lurks, private passions were beginning to roil the water—and Robert Moses' great enemy was beginning to move against him.

Highlight on Page 962 | Loc. 14744-50 | Added on Tuesday, September 22, 2020, 12:49 AM

If the reformers had looked at the Battle of the Battery Crossing in a broader perspective, however, they would have been holding not a “Victory Luncheon” but a wake. For in such a perspective—the significance of the battle in the history of New York City—the key point about the fight and its significance for the city’s future was not that the President had stepped in and stopped Robert Moses from building a project that might have irreparably damaged the city. The key point was that it had taken the President to stop him. The city’s own mayor, the elected representative of the city’s people, the personification of the city’s will, hadn’t been able to stop him. Neither had the city’s other elected officials—or its most wealthy, prestigious and influential private citizens, the “in group” or “establishment” that could, when united, usually count on carrying the day on any issue about which it was particularly concerned.

I’m going to stop here, as we’re only a third through what I saved and this is getting quite long. My full clippings can be seen here.

This is just a taste of the audacity of this dude, there’s a lot more to the book, including his eventual fall from grace. It can be difficult to approach due to its length, but I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone who is even remotely interested in history, urban planning, New York, and the creation and use of power. There’s something here for everyone.